Low effective corporate rate not an argument against tax cut

President Trump says that U.S. corporations face the highest tax rates in the world, whereas opponents of his tax reform say that “actual” corporate tax rates are in line with other countries. What gives?

The president is referring to the rate that applies to taxable corporate income, known as the “statutory rate.” The federal statutory rate is 35 percent, and the combined federal-state corporate rate is typically about 39 percent. This rate is greater than anywhere in the industrialized world.

{mosads}But the statutory rate does not apply to all of the income-generating activities of corporations, because some of those activities create deductions that can be subtracted from business income for corporate-tax purposes.

Debt-financed activities are a good example, because the income they generate goes corporate-tax free to the extent that it can be distributed to investors as interest income.

Intellectual property investments are another example, because they are not obviously attached to a physical location, thereby helping accountants assign their returns to Ireland and other low-tax jurisdictions.

As a result, corporations are paying less than 39 percent of their income to state and local treasuries. The Government Accountability Office estimates 17 percent, which it calls the “effective rate.”

It might seem that the 22-percentage-point difference results in a free lunch for corporations at the government’s expense. But the opponents of corporate tax reform are mistaken to ignore the fact that the corporate tax has corporations paying a lot more than the checks they write to government treasuries.

The Internal Revenue Service (under the Obama administration) estimated that corporations and partnerships pay over $100 billion annually in complying with business-tax laws, including their costs of recording, keeping and hiring paid tax professionals. Compliance costs are not checks written to the government, but are real costs nonetheless.

In fact, the high compliance costs are a symptom of the low effective rate because business-tax deductions are a complicated enterprise. Corporations are paying for some of their 22-point savings in terms of the extra compliance costs that come with complicated tax strategies.

More important, our economy is less productive because taxes have induced investors to pursue tax-favored activities beyond what value creation would dictate. The most vivid example is the housing sector, where returns have been depressed by a factor of two or three because those returns are essentially tax free.

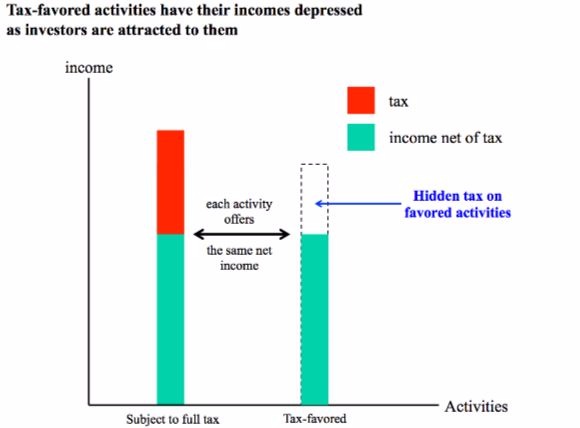

In other words, by having so many deductions, the corporate tax involves a substantial hidden tax on businesses beyond what they pay the government, with the extra payment in terms of lost income. The chart below illustrates by splitting the economy into two kinds of activities: those that pay full tax and those that are tax favored.

If nobody adjusted their investment plans, the tax-favored activities would be a great deal — they would earn the amount up to the dashed line and owe no tax. But there is no free lunch. The tax favors induce investors to engage more in those activities.

Their movement depresses the income accruing there — otherwise nobody would be willing to do the activities subject to full tax. The chart illustrates this by showing how the income ultimately earned has been depressed enough so that the net-of-tax earnings is the same for both types of activities.

The low effective corporate tax rate is therefore not an argument against President Trump’s call for tax reform. That low rate is further evidence of the economic damage done by the tax, as businesses pay to comply and pay by accepting comparatively low-return investments.

Because the effective rate only counts costs in the form of payments to government, a low effective rate is telling us that cutting the corporate tax will benefit economic performance far more than it will cost government treasuries.

Casey B. Mulligan is a professor of economics at the University of Chicago. His work has been featured regularly in The New York Times.

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed..