The shallow opposition to Keystone

With arguments so shallow, one would think that they would choose to maintain a dignified silence. The arguments are those offered in opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline, on both environmental and economic grounds, and “they” are the “environmentalist” (truly a term straight out of Newspeak) opponents of the project, most recently the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC).

And with respect to silence, whether dignified or not: One would be wrong. Danielle Droitsch, the director of the NRDC “Canada Project,” writes on Real Clear Politics in opposition to the pipeline as follows:

- Keystone XL “would significantly worsen climate change,” and by “trigger[ing] a boom in the development of Canadian tar sands oil [it] would be a climate disaster.”

- The pipeline “would threaten jobs and communities … with spills.”

- The pipeline would increase tar sands production because “shipping tar sands [oil] by rail to the Gulf Coast has proven too expensive.”

- The project “would create 35 permanent jobs … [and] 1,950 temporary jobs during a two-year construction” period.

- The pipeline would threaten “America’s heartland” as it would pass within a mile of more than 3,000 drinking water and irrigation wells … [and] cross more than 1,000 rivers, lakes, and streams.” And: “There were nearly 6,000 spills and other serious incidents from 1994 to late 2014.”

- “Most Canadian tar sands crude would be refined and shipped overseas.”

Wow. With respect to climate change, Keystone XL would transport 830,000 barrels per day of Canadian crude oil, the total greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) from which would be 147 to 159 million metric tons per year on a life-cycle basis. In the extreme case in which the oil does not displace any other crude oil production elsewhere in the world, the increase in GHG emissions would be about 0.4 percent of the world total, a fact that belies Droitsch’s mindless factoid about some sort of equivalence between Keystone XL and “6 million cars.” Nor does Droitsch offer us an actual estimate of the temperature effect of the marginal Keystone XL greenhouse gas emissions. So what would that effect be in the year 2100? If we apply the National Center for Atmospheric Research climate model, using the highest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assumption about the climate sensitivity of increasing greenhouse gas concentrations, that temperature effect would be about four ten-thousandths of a degree, a number rather inconsistent with Droitsch’s empty rhetoric about “a climate disaster.”

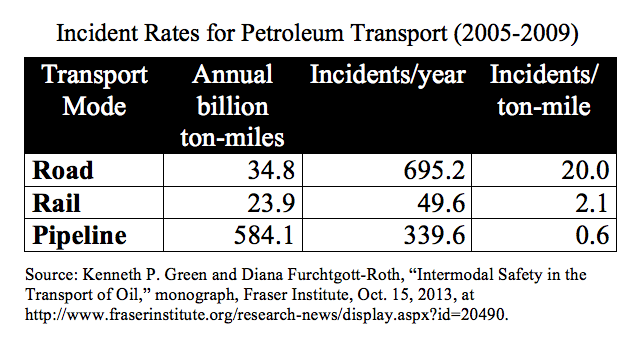

Moreover, transport of oil by pipeline is substantially safer and lower-risk in terms of spills than transport by rail or truck, the real-world alternatives to Keystone XL. An examination of the data, which Droitsch fails to offer, shows that for crude oil and petroleum products in the U.S., pipelines carry about 70 percent of the ton-miles; the respective figures for water transport, trucking and railroads are 23 percent, 4 percent and 3 percent. If we ignore water transport (not relevant as an alternative for Keystone XL), the data on incidents — explosions or fires, releases (spills) of five gallons or more, fatalities, personal injuries requiring hospitalization, or all-inclusive property damage exceeding $50,000 — are summarized in the following table.

With respect to the argument that the pipeline would increase Canadian production: That this oil will be produced with or without the pipeline is a given, largely because fixed (or sunk) costs are uniquely high relative to production costs for oil sands output. True enough: The Canadian oil competes with Mexican and Venezuelan crudes, so that higher transport costs for the most part reduce net prices received by the Canadian producers. But production costs (once the fixed costs are invested) for the existing Canadian oil sands projects are about $30 to $40 per barrel. Accordingly, the cost of rail transport to the Gulf Coast is irrelevant: The oil will be produced, but refined in Northern or Eastern refineries, thus yielding an inefficient allocation of crude oil geographically, with lighter oil from hydraulic fracturing operations sent to the Gulf Coast refineries despite the fact that those facilities are optimized for heavier crudes. (That is why construction of Keystone XL would be likely to reduce gasoline prices on net.) Without the pipeline, increased demand for rail transport will continue to create railroad capacity constraints, and thus increased incentives to expand that capacity over time. The upshot: The Canadian oil will be produced, and the only questions are where it will be refined and at what higher cost. Over the longer term, investment in Canadian production capacity is likely to be reduced in the face of the recent sharp reduction in world oil prices, but that has nothing to do with Keystone XL.

With respect to the argument that the employment created by the project would be trivial: Whether that is true or not remains to be see — it actually is not an issue with which government policy ought to be concerned — but the hypocrisy of the environmental left on this issue is breathtaking given the eternal “green jobs” argument used to justify heavy subsidies for wind and solar power projects. An example is the Ivanpah solar power monstrosity in the California Mojave desert. Put aside the huge costs, huge subsidies and huge environmental damage attendant upon that project. Merely compare the “jobs” outcomes for Ivanpah — applauded by the environmental left — with the “35 permanent jobs … [and] 1,950 temporary jobs during a two-year construction” period that Droitsch views as too small to justify Keystone XL. Ivanpah employed about 2,600 construction workers and support staff over three years, and created about 90 permanent positions, numbers not very different from those about which Droitsch sneers in the context of Keystone XL. (I shunt aside here the adverse employment effects of the Ivanpah costs and subsidies necessarily created in other sectors.) Because Keystone XL would not receive subsidies, the associated employment would improve labor productivity, a condition very different from that attendant upon the subsidized distortions characterizing “renewable” power generally and Ivanpah in particular.

As for the purported threat to “America’s heartland”: In 2012, there were about 1.7 million miles of oil and gas pipelines in the U.S. The U.S. portion of Keystone XL would be 875 miles, thus adding five one-hundredths of a percent to the U.S. pipeline system. It is not quite clear what Droitsch means by “nearly 6,000 spills and other serious incidents from 1994 to late 2014” — Which spills from what operations and what kinds of “serious incidents”? — but pipeline transport is vastly safer than rail transport in every dimension, as noted above. Does Droitsch really want to argue the comparative safety issue? Seriously?

Droitsch actually seems to believe that the prospective export of the petroleum products produced from Canadian oil somehow is a meaningful argument against the pipeline. Huh? The U.S. is part of a world market for crude oil and petroleum products, and the effects of changes in international prices, or, say, of supply disruptions are independent of the direction and magnitude of such trade flows. “Energy security” thus is a rather empty concept, however much it is viewed as serious inside the Beltway, but there is little evidence in Droitsch’s discussion that she understands how to think about that issue. But it is one more weak argument among many; why not just throw it in to see who salutes?

The emptiness of Droitsch’s arguments is illustrated by her repeated use of the phrase “carbon pollution,” a term that is little more than political propaganda designed to answer the basic policy question before it is asked. Carbon dioxide is not “carbon,” and it is not a pollutant. Some atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide is necessary for life itself, and unlike the case for the criteria pollutants — carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, particulate matter and sulfur dioxide — less carbon dioxide is not necessarily better. Whether or not carbon dioxide is harmful on net if atmospheric concentrations rise above some level is hotly(!) debated — even the IPCC recognizes the uncertainties — and depends heavily not only on the underlying climate science, about which there is much dispute, but also such value judgments as whose well-being ought to be maximized, how heavily we should discount possible but uncertain future effects and how to evaluate the tradeoff between impacts that are positive and negative. Those issues are crucial, but have virtually nothing to do with the increase in national wealth that Keystone XL would yield, an effect that the opponents of the pipeline view solely through an ideological lens.

Zycher is the John G. Searle scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed..