‘Deaths of despair’ on the rise among blue-collar whites

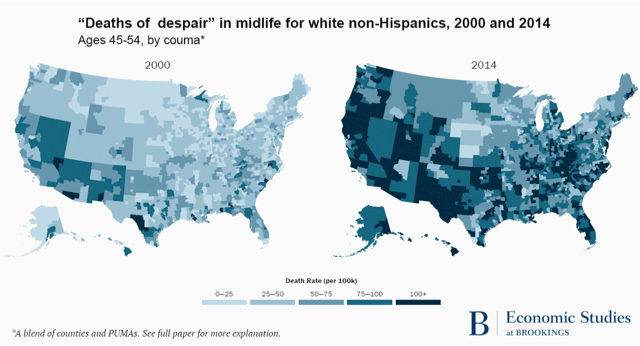

A decades-long trend of economic stagnation and social immobility may be to blame for a shocking increase in death rates among middle-aged white Americans, a new study finds, as the number of deaths caused by drugs, alcohol abuse and suicide reaches levels not seen in generations.

For nearly a century, advances in medical technology and healthy living have sent mortality rates of all Americans plummeting. But in recent years, a stark divide has emerged along educational and racial lines: as death rates plunge for minorities and well-educated whites, the number of whites without a college education dying in middle age is skyrocketing.

In a new study, Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton point to a sharp rise in what they call “deaths of despair,” deaths caused by drugs, alcohol poisoning and suicide.

At the same time, the medical progress that had sharply cut the number of deaths due to heart disease and cancer has plateaued, contributing to the overall increase in mortality rates.

{mosads}Middle-aged whites who have not attained a college degree are most susceptible, which the authors say may come from limited economic prospects not faced by their parents and grandparents. While older generations were able to build stable lives with the help of good factory jobs, those jobs are increasingly moving overseas, or disappearing thanks to automation.

“Traditional structures of social and economic support slowly weakened; no longer was it possible for a man to follow his father and grandfather into a manufacturing job, or to join the union,” the authors write.

That generational shift contrasts with the experience of African Americans and Hispanic Americans, many of whom are living better lives than their parents or grandparents, even as they continue to lag whites in educational or economic attainment. Polls today show minorities believe their children will have better lives than they do, while whites tend to worry their children will not have lives as good as their own.

The numbers are stark: Between 1998 and 2015, the mortality rate for men between the ages of 50 and 54 who had attained a bachelor’s degree fell from 349 per 100,000 to 243. The mortality rate for the same age cohort among whites who had not attained a college degree rose from 762 per 100,000 to 867.

Blacks and Hispanic Americans, both those who had attained a college degree and those who hadn’t, continued to live longer lives as mortality rates fell.

Among blacks, mortality rates fell across all ages between 1999 and 2015. Among whites without a degree, mortality rates rose among all age groups. At the turn of the century, whites without a college degree were 30 percent less likely to die in middle age than were African Americans; today, they are 30 percent more likely to die than are African Americans of the same age.

Whites without a college degree have experienced both real and perceived decreases in their economic and physical well-being. Real wages for those without a college degree have fallen in the decades since the 1970s, while those people are far less likely to say they are in excellent or good health as those who have a college education.

“We see our story as about the collapse of the white, high school educated, working class after its heyday in the early 1970s, and the pathologies that accompany that decline,” Case and Deaton write.

As economic prospects have waned, the number of non-college educated Americans in the workforce has shrunk, with the epidemic of opioid addiction taking its toll.

Men without a college degree are less likely to participate in the labor force at any given age than those born before 1940, the authors found. The economist Alan Krueger wrote in 2016 that half of men who are not in the labor force are taking pain medications, and two-thirds of those men are taking a prescription painkiller.

Though they say increased opioid use is not a fundamental factor in the rise of deaths of despair, the growing supply of the painkiller has “added fuel to the flames, making the epidemic much worse than otherwise would have been,” the authors write.

The phenomenon of rising deaths among whites appears to be solely American. A comparison across 10 European nations, plus Australia, Canada and Japan, finds mortality rates declining by a significant margin on an annual basis. Only American non-Hispanic whites have experienced an increase in mortality rates.

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed..