The G20 membership needs a drastic demographic edit

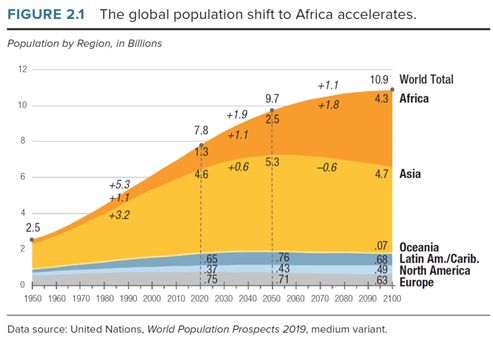

The G20, which met last month, is missing an important opportunity when it comes to addressing the major challenges of the coming demographic upheaval. Given the projected population shift to Africa (see chart), the inclusion of only one African country in the membership is a glaring oversight, if indeed the forum seeks to be forward-looking.

Created in 1999 as a collaboration among advanced and developing economies, the group membership needs a demographic edit.

The G20 was created to focus on economic and social challenges facing a broad group of countries, a group more representative than just the G7 countries. But since then, global challenges have changed enormously. Because many of the coming economic and political challenges we face are rooted in the dramatic population changes expected by the midcentury and beyond, we should pay close attention to demographically affected countries. It would help to adjust the G20 membership to anticipate future challenges and to include major stakeholders.

The agenda for the November G20 meeting in Bali focused on global health, sustainable energy transition and digital transformation. All three priorities will be dramatically affected by global population change. In addition to South Africa, the sole African member several African countries and regional organizations have attended G20 meetings as invited guests to broaden the scope of interests. As those interests become increasingly important globally, guest status no longer seems adequate.

It is not only logical to include affected parties, but it is imperative that key stakeholders in the demographic upheaval be included as full members in the deliberations. Including such stakeholders in future meetings will improve the focus and effectiveness of the deliberations.

As discussions evolve regarding invited guest versus full membership status, it will help to understand key aspects of the coming population changes.

The global population distribution is rapidly shifting toward Africa. As projected by the United Nations, the continent of Africa, with less than 20 percent of the world’s total population today, will account for nearly 60 percent of projected population growth over the next 30 years and nearly ALL the projected growth by the century’s end. As a result, Africa will account for more than one-quarter of the world’s population by the midcentury and nearly 40 percent by 2100.

Even more concerning, about 40 percent of projected global population growth is expected to occur in the least developed countries — those with the lowest capacity for addressing the coming challenges, and those most vulnerable to the impacts of economic and environmental shocks. Most of these countries are in Africa and most have rapidly increasing populations. This vulnerability and weak infrastructure for health and education make global attention to Africa even more important.

Relatedly, fueled by high fertility rates, Africa will account for over three-quarters of working-age population growth in the coming decades, so the absence of any large or fast-growing African countries in the G-20 seems even more glaring. In contrast, many large and emerging economies face shrinking workforces over the next few decades. The slower growth in the working-age population and shrinking workforces around the world have garnered increasing attention among policymakers seeking to increase labor supply and boost productivity gains.

With half of the largest economies facing shrinking workforces in the next 20 years, it is only logical that they seize the opportunity to capitalize on Africa’s potential as both a source of labor, as well as a target for educational advances. In addition to investing in Africa’s natural resources, investors might see long-term potential in human capital investment. Education is the primary avenue for reducing explosive population growth and enhancing economic prospects for the burgeoning youth population of Africa.

The lens of migration offers further evidence of the glaring omission of African countries from the G20. Two conditions will likely prompt increased outmigration from Africa. First, economic growth is not keeping up with population growth, so Africa’s young people face dim economic prospects, a condition likely to spur outmigration. Second, the impact of climate change will exacerbate economic weakness and further spur outmigration.

If the goal of the G20 is to address coming challenges, it makes sense to revise the G20 membership to include more countries that will be directly affected by the coming demographic upheaval. In the words attributed to hockey great Wayne Gretzky, it makes sense to skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been.

Adele M. Hayutin is an Annenberg Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. She is the author of the book, “New Landscapes of Population Change: A Demographic World Tour.”

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed..