Cuts to scientific research portend a lost generation of innovation

Lost among the debates about healthcare, immigration and tax reform, there exist dangers to scientific and engineering research in the Trump administration’s proposed budget cuts.

The cuts are brutal — almost 20 percent at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, on top of cuts to all funds for the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy. Even more drastic cuts are proposed for all research activities related to the environment.

{mosads}As is the case with retirement savings, a little investment now pays off over the long term. Americans of all stripes recognize this fact. According to a 2015 Pew analysis, 83 percent of Democrats and 62 percent of Republicans support long-term government investments in research. Public support for science, according to the Pew analysis, is typically well above 70 percent.

Other countries have tried to slash government investment in research, while hoping to free-ride off the investments of private entities. The results have not been positive. The question is: Do we want to suffer the same fate? Should China become the new world leader in science and engineering research?

Let’s step back in time. You might recall Galileo, the 16th-century Italian scientist whose vision made Italy the center of world science. His research putting the Sun at the center of the solar system was rejected as “foolish and absurd” by those in power. These “foolish notions” resulted in the compass, thermometer, scales and pendulum clock — all with important commercial and military uses.

Then there is Sir Isaac Newton, who, in the early 18th century, helped England overtake Italy as the leader in science and engineering research. Newton is, of course, best known for deducing the laws of gravity and inventing calculus, both leading to countless innovations.

The British scientist had his own disagreements with the government of the day, opposing the policies of King James II, who wanted to limit those in government to the practice of a particular religion.

In the 18th Century, France challenged England for the lead in science. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, German was the language of science. The United States did not become the world leader until 1950, when it took advantage of possessing the only fully operational science and engineering research system in the world.

The United States established the National Science Foundation and, later, won the Space Race with Russia after that nation launched Sputnik during the Eisenhower years. Investments paid off as jobs were created.

Now, in the 21st century, is the U.S. heading for the same fate as those other global powers by cutting the science budget and letting China surge ahead?

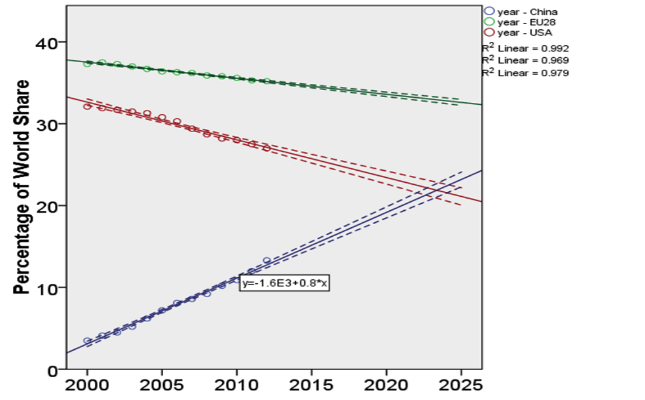

The signs point in that direction. Since 1980, China has rapidly moved to become the second-most productive scientific nation (in terms of publications) in the world, behind the United States. As China has risen in science, U.S. and European shares of published articles have declined, as seen below:

Many point out that the quality of Chinese science cannot rival other scientifically advanced nations. Those critics are correct for now, but this is changing, too.

While Chinese publications are not among the elite in top citations and prizes, their status is rising exponentially, while Europe, Japan and the U.S. remain flat or are dropping. The figure below shows the rise of China, the drop in the U.S. and the flat performances of European nations.

[[{“fid”:”130399″,”view_mode”:”original_image”,”fields”:{“format”:”original_image”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:””,”field_url[und][0][value]”:”Bornmann, L., Wagner, C.S., Leydesdorff, L. “,”field_folder[und]”:”1″,”field_free_html[und][0][value]”:””,”field_free_html[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”style”:””},”type”:”media”,”attributes”:{}}]]

Technology and industrial growth are closely tied to scientific research, and these are the engines that drive job creation. If science and engineering pioneers from other countries find it difficult to come to the United States — for education, conferencing and collaboration — they will take their aspirations elsewhere. We are already seeing the signs today — more international students currently go to Canada than go to the United States.

We cannot take for granted that the United States remains at the global center of science and engineering. If Congress does not act to stop these dramatic cuts to science and engineering research, the United States could lose its momentum and sacrifice its “seed corn,” leading to a lost generation of research and researchers and the resulting loss of societal, economic and employment impacts.

Deborah Stine is associate director for policy outreach at the Scott Institute for Energy Innovation and professor of the Practice, Engineering and Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon University. Caroline Wagner is affiliated with the Battelle Center for Science & Technology Policy, and Wolf Chair in International Affairs, John Glenn College of Public Affairs at Ohio State University.

The views expressed by contributors are their own and not the views of The Hill.

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed..