American and Chinese trade with Africa: Rhetoric vs. reality

On Aug. 4, President Obama welcomed leaders from across the African continent to Washington for a three-day U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit. One major topic of discussion, in addition to the political and security issues, will inevitably be how to enhance U.S.-Africa economic relations.

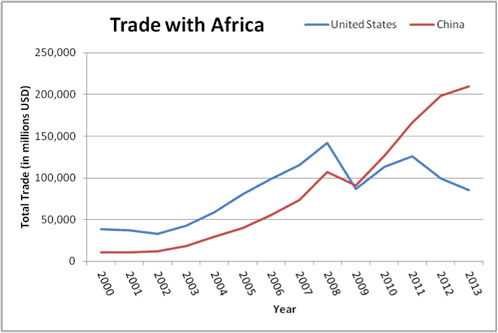

{mosads}Since 2000, U.S. trade relations with Africa have been dictated by the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). As a unilateral preference scheme of the U.S. to promote trade and investment in Africa, AGOA was meant to boost U.S. trade with Africa and the development of the continent. However, 14 years in, U.S. trade in goods with Africa has demonstrated a perplexing downward trend since 2011. U.S.-Africa trade dwindled from $125 billion in 2011 to $99 billion in 2012 and $85 billion in 2013. For the first five months of 2014, U.S.-Africa trade in goods totaled about $31 billion. At this rate, the total trade volume in 2014 could be well below $80 billion in a continuation of the declining trend.

In comparison, Beijing has been quite low-key in disseminating its Africa trade promotion efforts, although its trade with Africa has been growing exponentially. China surpassed the U.S. as Africa’s largest trading partner in 2009. China-Africa trade reached $166 billion in 2011, an 83 percent rise from 2009. The bilateral trade further increased another 19.3 percent to $198 billion in 2012, and passed the $200 billion threshold to $210 billion in 2013. In terms of trade volume, Chinese trade with Africa not only dwarfs U.S. trade with Africa, but the gap is as large as 2.5 times the magnitude of last year.

Note: U.S. data from Census Bureau. China data from Global Trade Atlas via Tralac.org.

The rhetoric and realities of American and Chinese trade with Africa present an interesting contrast. Despite the callings in the U.S. to boost economic relations with Africa and to “compete” with the expanding Chinese economic influence on the continent, the results seem less than impressive. On the other hand, although the Chinese have remained quieter about their Africa trade promotion, the trade figures have been growing fast.

The decline of U.S. trade with Africa is largely attributable to the watershed 2008 financial crisis. Before the crisis, U.S.-Africa trade had been progressively increasing, but aside from a short 2010-2011 rebound, it has fallen since. In efforts to explain the decline, much was made by some analysts of reduced remittances or uncertainty around the 2012 renewal of AGOA’s third-country fabric provision. However, while these dynamics might have affected certain countries, they did not necessarily have a major effect on the overall U.S.-Africa trade relationship.

Instead, the data point largely to just one culprit: oil and gas. In the wake of the financial crisis, African exporters faced a one-two punch: U.S. oil consumption began a 9 percent decline (from 20.7 million barrels per day in 2008 to 18.9 million in 2013) and the cost of oil dropped 70 percent from $140 per barrel to as low as $32 per barrel within a year. From 2008 to 2013, oil and gas exports from AGOA countries to the U.S. plummeted by 66 percent from $60 billion to $20 billion. By contrast, non-oil exports fell only $400 million, or about 6 percent, during the same period, and U.S. exports to those same countries actually grew. Because the U.S.-Africa trade relationship is so dependent on African oil exports, however, it was remarkably vulnerable to oil price shocks. Indeed, after oil, some of the next top U.S. imports from Africa (though far less in value) include precious stones, cocoa and ores — more commodities vulnerable to price shocks and reflective of a not-so-diversified trade relationship.

Source: Author calculations from AGOA information.

The most recent U.S. effort to turn this trade relationship around was released in Tanzania in July 2013 under the framework of Trade Africa. Among the goals in the initial phase, the plan intends to increase exports to the U.S. from the East African Regional Community (EAC) by 40 percent. To facilitate that goal, the U.S. plans to explore an investment treaty, operate a trade hub that will “provide information, advisory services, risk mitigation and financing … to U.S. and East African investors and exporters,” and advance its “Doing Business in Africa” campaign, which includes “trade missions, reverse trade missions, trade shows, and business-to-business matchmaking in key sectors.”

Admirable on the surface, it remains questionable whether the plan will come to pass. Forming a sustainable U.S.-Africa trade relationship would require not just growth, but also diversification away from reliance on commodities. Oil discoveries in the EAC may very well contribute to a 40 percent increase in U.S.-Africa trade, but such trade would still remain vulnerable to global price shocks. If instead, Trade Africa were to include sector-specific benchmarks for manufacturing or the EAC’s burgeoning tech sectors, any resulting growth in trade could be more resilient.

On Chinese trade with Africa, although the total trade volume has still grown in 2013, the speed of such growth has slowed down — from 19.3 percent in 2012 to 5.9 percent in 2013. Such a rate is also lower than the growth of China’s overall foreign trade: 7.6 percent in the same year. While the broad context is the slowdown of China’s economic growth and of its foreign trade, exports by Africa suffer in particular because, like the U.S., China’s demand for raw materials has declined.

China ran a small deficit of $24.6 billion in its trade with Africa, while its exports are still largely dominated by finished products including machineries, electronics, automobiles, textiles, etc. Meanwhile, despite the reiterated efforts that China would reduce the percentage of natural resources imports in Sino-African trade, natural resources remain dominant. In total, China’s crude oil imports from Africa made up 23 percent of China’s global imports in 2013, making Africa the largest exporter of crude oil for China.

China bears high hope for the development of Sino-African trade. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang pronounced the plan to double bilateral trade to $400 billion by 2020. As China struggles with its own economic restructuring, it has been hoped that emerging markets such as Africa would assist the process. China aims to transfer some of its labor-intensive and manufacturing sectors such as textile, garment and household appliances to Africa for an “alignment of industrial development strategies between China and Africa.” And to boost such a development, China is eager to contribute to the infrastructure of the continent, including active involvement in highway, railway, telecommunications, electric power and other projects that facilitate regional connectivity. At the same time, the ambition will translate into heightened investment efforts in Africa and a growing market for Chinese infrastructure contractors.

While these may be good news for Africa and Sino-Africa relations, they also have significant implications for the United States. Most evidently, if the U.S. is to successfully compete with China on economic engagement in Africa, the pressure is mounting. As the interest in a U.S.-China competition in Africa rises and people question whether the U.S. is losing out to China, it should be noted that if the U.S. is not enhancing its own investment and trade efforts in Africa anyway, portraying China as a threat does not necessarily help improve America’s position.

Despite enthusiastic rhetoric in some corners, U.S. trade with Africa seems on faulty footing and unlikely to grow. U.S. oil consumption remains down since 2008, and imports are now further held down by a natural gas boom at home. Non-oil trade between the U.S. and Africa is growing, but only modestly overall. U.S. businesses continue to view private investment in Africa as risky, and government actions to mitigate such risk will prove harder as Congress looks to eliminate tools like the Export-Import Bank. If the U.S. values a strong economic relationship with Africa, or seeks to balance a Chinese presence there, much remains to be done in both diversifying and growing trade.

Sun is a fellow with the East Asia Program at the Stimson Center and Rettig is a communications associate at the Brookings Institution.

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed..