The county that gave Clinton only 5 votes

Hillary Clinton won just five votes from Texas’s King County in last year’s presidential election, a stunningly low total from what was once a true-blue source of votes for Democrats.

John F. Kennedy won 77 percent of the vote in King County in 1960, three years after the town of Guthrie was immortalized in “On the Road.” Author Jack Kerouac would have visited a deeply Democratic bastion when he rushed through Guthrie, but more than 50 years later the area has turned almost completely against Democrats, highlighting a dramatic change in voting patterns that both parties are struggling to manage.

Clinton’s five votes in King County represented her lowest total of any county in America. Trump received 149 votes in the county, which is an hour and a half east of Lubbock.

{mosads}When Richard Nixon won the White House in 1968, he scored a narrow plurality over Hubert Humphrey in Prince George’s County, Md., just across the Anacostia River from the nation’s capital. Forty-eight years later, Donald Trump won 8.4 percent of the vote there, his worst performance outside Washington, D.C., where he won just 4.1 percent of the vote.

As the American electorate grows more diverse, and as a rising generation of millennials begins supplanting formerly dominant baby boomers, two nations that live side by side are increasingly walling themselves off from each other.

That divide is a conscious choice, one that experts say influences how we interact with each other, where we move, what news we consume and, increasingly, how we vote.

This is the ninth part in The Hill’s Changing America series, in which we explore the trends shaping society and politics today. Those trends — the rising success of large metropolitan areas contrasted with the struggles of rural counties, the diversity of millennials and the political polarization of boomers — have conspired to create what demographers call the Great Sort.

And all signs indicate the Great Sort is intensifying.

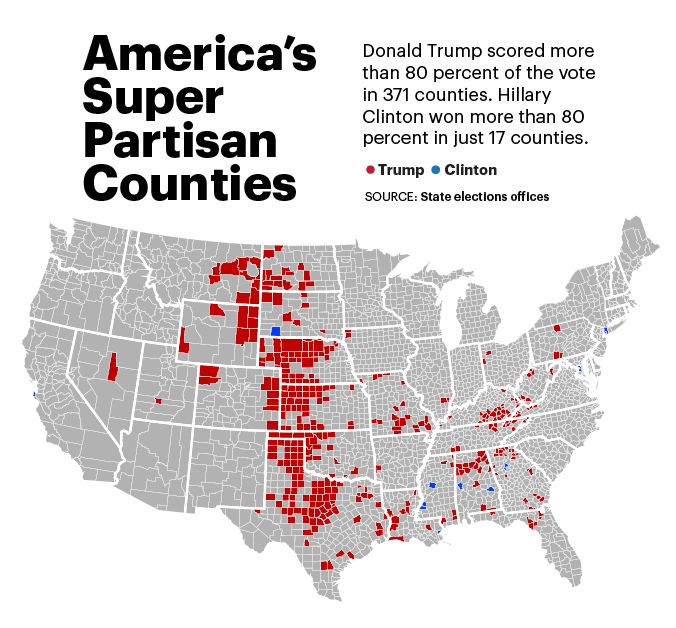

Nearly 59 percent of Americans — almost 187 million of us — live in counties that voted for Clinton or Trump by 20 or more percentage points. An incredible 1,559 counties gave Trump more than 70 percent of the vote in 2016, and 99 gave Clinton the same percentage.

That’s a marked contrast from the 2000 election, when another Democratic candidate also won the popular vote while losing the Electoral College. That year, George W. Bush took 70 percent of the vote in just 546 counties. Al Gore won the same percentage in 46 counties.

The increasing divide between Red America and Blue America has sewn animosity and distrust among even the most patriotic among us as partisan echo chambers reinforce notions that those with ideas that run counter to our own are out for nefarious purposes.

Much of those ill feelings come, experts say, because Americans have increasingly limited opportunities to interact with those on the other side of the political aisle, because Red America and Blue America look distinctly different and view the other with growing suspicion, and because the two have experienced vastly different recoveries after the Great Recession.

“Our demographics have become tethered to our partisanship in a way that wasn’t the case in much of the 20th century,” said Paul Taylor, a senior fellow at the Pew Research Center and author of “The Next America: Boomers, Millennials and the Looming Generational Showdown.” “It gives us the incredible ugliness of our politics in 2017.”

The sorting taking place now is based on a handful of factors: Rising birthrates and immigration among nonwhite communities mean urban America is growing faster than rural America. Young adults, who tend to be more liberal, are choosing to live among those who think and act as they do. And the internet has given us the ability not only to communicate with those who think like us, but also to find out where they live.

“People tend to live among people who are like them, for economic reasons, for cultural reasons,” Taylor said. “We all have the ability to know more about each other and to modify our behaviors accordingly, including to be more efficient about living among people who look like us.”

Living among those who resemble us even extends online: Just 23 percent of the average person’s Facebook friends claim an opposing political ideology, according to the company’s internal research from 2015.

At a national level, the electorate’s sorting has taken place after a similar shift among the two major political parties. Southern Democrats were once much more conservative than their northern colleagues, and Northern “Rockefeller Republicans” were more liberal than Southern and Western Republicans. That is no longer the case.

Today the two sides are much more ideologically homogenous: 94 percent of all Democrats are more liberal than the average Republican, and 92 percent of all Republicans are more conservative than the average Democrat, according to Taylor’s research. Two decades ago, just less than two-thirds of Republicans and 70 percent of Democrats were farther to the right or left, respectively, of the other party’s average voter.

That homogenization is manifesting in the way Republicans and Democrats view each other. Fifty-eight percent of highly engaged Republican voters say the Democratic Party makes them feel angry or frustrated; virtually the same number of highly engaged Democrats said the same of Republicans.

In 1994, just 21 percent of Republican voters said they had a very unfavorable view of the Democratic Party. Today, that number is 58 percent. Among Democrats, the number who say they view the GOP very unfavorably has spiked from 17 percent to 55 percent over the same span.

To be certain, the internet and the rise of specialty media have contributed to those worsening feelings. Turn on Fox News or click on Breitbart and one is likely to see a story critical of Democrats; turn on MSNBC or head to Vox and one is likely to encounter negative information about Republicans.

There is little crossover in audience, even online: The Facebook research showed just 29 percent of news that shows up in someone’s feed cuts across party lines, and only a quarter of the stories people click on runs counter to their own political beliefs.

“The days are gone when everyone queued up the nightly news on broadcast TV to consume their political information,” said Mark Stephenson, a Republican data and demographics expert. “Now, voters have the ability to self-select sources, largely more and more digital in nature, which tend to reinforce and create the more partisan divide we now see.”

The widening divide has changed the way both Democrats and Republicans run their political campaigns. Presidential campaigns in recent years have become more negative, bent on either depressing a rival’s vote or inspiring one’s own base to show up.

Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign team buried Republican nominee Sen. John McCain (Ariz.) under more negative advertisements than any previous campaign in history — until his 2012 campaign eclipsed them in the race to define Mitt Romney and until 2016, when Clinton’s team ran an almost entirely negative campaign against Trump.

Said another way: Mobilizing voters has become more politically profitable than persuading those in the middle to join a side.

The vastly different experiences of Red America and Blue America since the end of the recession have contributed to a political sort as well, said Tom Bonier, a Democratic demographics analyst. While big cities and suburban areas have recovered and grown, rural America is struggling just to return to pre-recession levels.

“The best predictor for how you were going to vote in this election was how you felt about the economy,” Bonier said. “If you felt like the economy was in fair, excellent or good condition, you were overwhelmingly likely to vote Clinton.”

Stephenson said the partisan divide is becoming a problem for both parties. Democrats, increasingly relying on voters in liberal urban cores, must address a set of more liberal issues with which the rest of the nation might not be comfortable. Republicans, increasingly relying on voters in conservative rural bastions, face a math problem as those areas shrink.

It is the clash of those two populations — younger millennials in urban centers and older boomers in rural territory — who drive the politics of today, Taylor said.

“In the long run, we are going to have a very different electorate that supports a more conventionally liberal set of policies. But we are in a very slow walk to the long run,” Taylor said. “You will have a backlash to that, and we are right in the middle of that right now.”

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed..