How ‘Never Trump’ voters saved Republicans’ Senate majority

Donald Trump became the first Republican presidential candidate in 28 years to win Pennsylvania and the first GOP candidate in 32 years to win Wisconsin’s electoral votes.

At the same time, Sens. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.) and Ron Johnson (R-Wis.) won reelection, in both cases overcoming polling deficits that showed them trailing their Democratic opponents.

{mosads}On its face, it makes sense that if a Republican president won a state, a Republican senator would win reelection. But the underlying data shows Trump, Toomey and Johnson took very different paths to victory. Toomey and Johnson took advantage of an increasingly rare specimen of voter, the type willing to split their tickets between candidates of different parties running for different offices.

The two incumbents triumphed and Republicans retained their narrow Senate majority because of the occasional voter who showed up to cast a ballot for Trump, but also because of “Never Trump” voters. This group leans Republican in any given election, but they could not bring themselves to cast a ballot for the party’s brash presidential nominee.

This is the fifteenth story in The Hill’s Changing America series, in which we examine the demographic and economic trends driving American politics today. Those trends have led to a starkly divided nation, one in which few voters are willing to split their ballots between candidates from different political parties.

The decline of the split-ticket voter helps explain the polarization dividing the nation’s politics today. It also helps explain why Trump has a lower approval rating among college-educated voters than among those without a college degree.

Political science research suggests those who pay the most attention to the news, those with higher levels of education — and, therefore, those more likely to have heard Trump’s most inflammatory comments — are much more likely to split their tickets. Those who are less likely to consume news, in both political parties, are more hardened partisans.

But split-ticket voters do exist, and both Democrats and Republicans have made concerted efforts to win them over.

“If we don’t reach out to the American people, show them what we stand for and make sure they know we hear them, are listening to them, that we are going to focus on them, that we understand the constraints they are facing every day, that wages are not keeping up with the cost of living, and if we don’t do something to show them what we are going to do about that to make things better for them, I don’t know if we will ever earn their trust back,” Rep. Ben Ray Luján (N.M.), who chairs the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, told The Hill in an interview.

In Pennsylvania, Toomey won reelection by 84,000 votes, while Trump carried the state by 44,000.

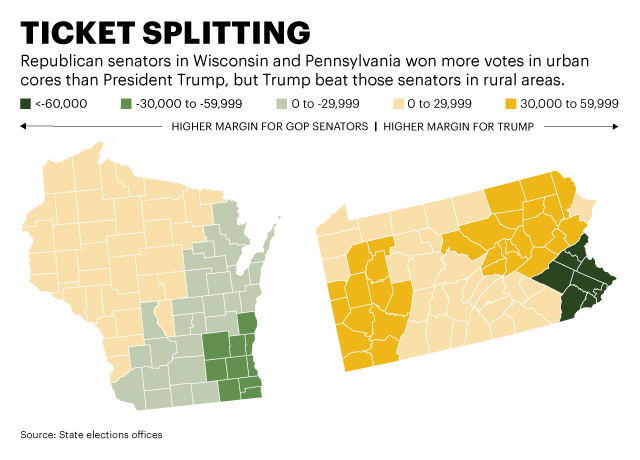

Democrats typically run up the score in the Philadelphia area, and both Clinton and Toomey’s opponent, Katie McGinty, followed the same playbook. Clinton beat Trump in those eight counties by a combined 647,000 votes. But McGinty beat Toomey in those counties by just 456,000 votes, a difference of 190,000 votes — more than twice Toomey’s statewide margin of victory.

Toomey outperformed Trump in Philadelphia and in the four collar counties that surround the city. McGinty received fewer votes than Clinton did in all eight counties that make up the Philadelphia media market.

In Wisconsin, Johnson won by a margin of 99,000 votes, while Trump carried the state by just 23,000. Like Toomey, Johnson overperformed Trump in the state’s most populous region: He won more votes than Trump did in all 10 counties that make up the Milwaukee market.

In both states, Trump vastly outperformed Toomey and Johnson outside the big urban cores. Trump won more votes than Toomey in every media market in Pennsylvania except the Philadelphia market. Trump won more votes than Johnson in all but the Green Bay, Madison and Milwaukee markets.

“That’s a story of Trump being weaker than normal in the suburbs, but he also was a lot stronger in the rural and industrial communities than most Republicans were,” said Brad Todd, a Republican strategist who watched both states closely. “In non-metropolitan America, Trump outran the Republican brand. In metropolitan America, he’s running behind.”

While the presidential campaign veered from debates on international trade to immigration, the economy and jobs, Toomey and Johnson focused more on local issues, according to advisers who steered their campaigns.

Toomey and Johnson worried about voters who were unhappy with Trump’s behavior and actions.

In Pennsylvania, that meant Toomey’s team had to be most concerned with upscale voters in the collar counties, who might opt to stay home rather than vote for Trump.

“Those voters prefer Republicans. They’re ancestrally Republicans,” Todd said. “They just couldn’t get comfortable with Trump himself. They felt there were too many social recriminations if they voted for Trump.”

Toomey’s campaign divided potential swing voters into nine separate buckets, based on issues they cared most about. Those voters saw messages about the senator’s work on measures supporting local police departments, on the opioid crisis and on gun control in their Facebook feeds.

Johnson, meanwhile, spent much of his time in northwest Wisconsin pledging to take the grey wolf off the Endangered Species List. He also worked on a deal to allow those in the Minneapolis media market, which covers much of western Wisconsin, to see Green Bay Packers games on Sundays.

Both candidates targeted Republican voters most at risk of sitting out the election with a pledge to fill a vacant Supreme Court seat with a conservative justice.

But ticket splitters are increasingly becoming a rare breed. As partisan attitudes have hardened, the number of voters willing to split their tickets has declined substantially.

Voters once felt free to elect members of different political parties to different offices. For most of the 20th century, it was not uncommon for a presidential candidate to carry more than 100 congressional districts represented by a member of the other party.

Many of those districts were in Southern states, where races for Congress were virtually completely controlled by the Democratic Party, while Republican presidential nominees cleaned up in the Electoral College. Between 1972 and 2012, Southern congressional districts voted Republican for president and Democratic for Congress a whopping 427 times, according to an analysis by the Pew Research Center.

The shoe fit the other foot as well: In 1992 and 1996, Bill Clinton won more than 50 congressional districts held by Republicans. And in those elections, a total of more than 100 districts favored one party for Congress and the other for the presidency.

Beginning in 2000, fewer than 100 districts have split their votes in each presidential election. In 2012, just 17 Republican-held districts voted for President Obama, and only nine Democratic-held seats chose Mitt Romney. Four years later, Trump won 12 districts held by Democratic members of Congress, and Clinton won 23 seats held by Republicans.

In 2016, every single Senate contest broke the same way as the presidential race, for the first time since Senate seats went to direct elections a century ago.

(If there is one place where split ticket voters still exist, it is in gubernatorial races: Five of 11 races in 2016 broke against the party that won the state’s electoral votes. A Democrat won the governorship in West Virginia even as Trump won the state by a massive margin, and a Republican won Vermont’s top job even as Clinton dominated the Green Mountain State.)

Today, most voters have deeply polarized political views. The Pew Research Center has found that nearly 6 in 10 Republicans and Democrats say they see the other party in a strongly unfavorable light, a threefold increase since the mid-1990s. And a majority say the other party’s agenda makes them feel scared or anxious.

The steep decline of ticket-splitting districts has coincided with a rise in partisan homogeny in Congress. Democrats and Republicans vote as partisan blocs much more often than they have in the past, in large part because they have little incentive to cooperate with the other side — and those who do face the threat of a primary challenge back home.

That presents a challenge for Republicans, who must hold together a base of populists who turned out for Trump and conservatives who want to see the GOP’s agenda passed. Without achievements in Congress, Todd said, that coalition will be difficult to hold.

“Republicans in Congress need to put points on the scoreboard,” he said. “You need to help the president achieve the things that will keep the populists engaged, and also do the Republican things that keep the suburbanites Republican.”

But it also represents a hurdle for Democrats, who find themselves competing on a narrower playing field. The party must win back all 23 Republican-held seats Clinton won in 2016, plus at least one additional district Trump carried, to contest for a majority in Congress next year.

“We’ll need a broad coalition” to win back the majority, Luján said. “We have to be a big family in order to win the House back.”

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed..