Stagnant population growth sets up close battle for 435th House seat

New data from the Census Bureau show America’s population growth stagnating in the final years of the decade, as declining immigration rates and an aging population run headlong into the coronavirus pandemic that pumped the brakes on migration within the U.S.

The consequence is likely to be a fraught battle over the reapportionment process that will follow the bureau’s release of official population figures early next year.

The estimates suggest that two states in particular — Alabama and New York — will spend the next few weeks on pins and needles, waiting to see which state wins the 435th seat in the House of Representatives.

If reapportionment took place on the basis of the new estimates, Texas’s delegation to the House of Representatives would grow by three seats, Florida’s by two, and Arizona, Colorado, Montana, North Carolina and Oregon would all add an additional seat.

On the losing end is New York, which stands to see its delegation to Congress cut by two seats. California, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and West Virginia would all stand to lose one seat. In California’s case, it would mark the first time since statehood that it has lost a seat in a round of reapportionment.

The latest figures are a holiday season gift to Alabama. For most of the decade, population estimates have suggested New York would lose only one seat, and that Alabama would also lose a seat.

“For the most part, Alabama has missed out on the larger demographic shifts towards the Southern states. The new reports provide a small ray of hope that Alabama may be starting to tap into some of that growth,” said Robert Blanton, chair of the political science department at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

But both New York and Alabama must wait on final Census Bureau figures — not estimates from July 1, but from the formal decennial count on April 1. And the margins are so close that neither can plan on the estimates: Alabama appears to have retained its seventh seat by a margin of just 6,210 residents, and the estimates show New York losing its 26th seat by just 24,430 people.

Making matters more complicated, several legal challenges to census counts could throw all the estimates into chaos. The Supreme Court said last week that it was premature to rule on whether the Trump administration could exclude undocumented immigrants from the reapportionment data that will award House seats to states.

“All of this stuff is showing how close these population estimates are and how indeed there could be changes in the apportionment, depending not only on what the Supreme Court does but clearly just on the straight population numbers themselves,” said Kimball Brace, a demographer who runs the nonpartisan firm Election Data Services.

The figures released Tuesday are estimates of yearly population changes that ended on July 1, 2020, based on official census counts in 2010. According to those estimates, the United States added just over 1.1 million residents in the last year, an annual rate of 0.35 percent — the lowest annual growth rate in any year since the bureau began making yearly estimates in 1900.

Sixteen states experienced a net loss of population over the last year, the figures show, and six states — Connecticut, Illinois, Mississippi, New York, Vermont and West Virginia — have fewer residents today than they did when the last census was conducted in 2010.

Some experts raised questions about the quality of this year’s census, hindered both by the challenges of counting people in the midst of a pandemic and by the Trump administration’s efforts to rush the count and curtail follow-up procedures. The expedited counting, some cities and states worried, may overlook their hard-to-count populations, which are disproportionately made up of minorities, rural residents and the undocumented.

“These are all population estimates. They’re not final census counts. The real issue is we don’t know how well the census was actually taken this year,” Brace said. “It’s possible that the problems with the census this year will really show up next month when the apportionment numbers come out.”

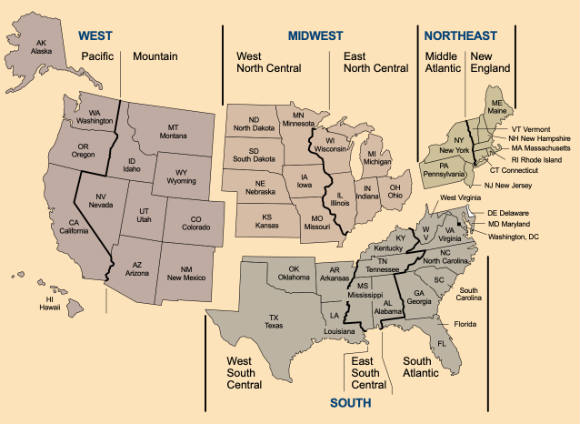

The latest figures show a continued population drift away from Northeastern and Rust Belt states and into Southern, Western and Mountain West regions.

Since the beginning of the 20th Century, the nine states that make up New England and the Mid Atlantic — stretching from Maine to the Mason-Dixon line on Pennsylvania’s southern border — have seen their congressional representation drop from 108 seats to 74 seats, if the current projections hold.

Seven states in what the Census Bureau calls the West North Central region, from the Canadian borders of North Dakota and Minnesota south to Kansas and Missouri, have seen their delegations shrink from 54 seats to 28, according to the estimates.

The delegations from the five Pacific Coast states, including Alaska and Hawaii, which joined the union in 1959, will have grown from 13 seats to 71 seats. The eight states in the Mountain West will see their combined delegations grow from eight seats at the turn of the last century, before Arizona and New Mexico joined the union, to 34 seats today. Those eight states have added 10 seats in just the last three decades.

Both the South Atlantic region, from Maryland to Florida, and the West South Central, which includes Texas and its three neighbors to the north and east, have been the beneficiaries of the northern population drain in the last century. Texas alone has doubled its delegation since the reapportionment process that took place after the 1910 census, while Florida’s delegation has grown sevenfold, from four seats to 29, over the same time, assuming the current estimates hold.

“The relative shift of population and seats from the Northeast, Midwest and, for the first time, California and into the South and Southwest isn’t a new trend but does reflect the decades-long shift that has had political and economic consequences, at least for the balance of power among states and regions in the House,” said Charles Franklin, director of the Marquette Law School Poll, who analyzed the new population data.

“That process will continue.”

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed..